Previously Unpublished Interview with Ross Macdonald

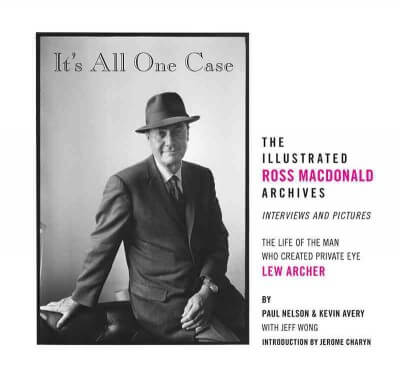

(We are very proud to share this interview with Ross Macdonald from It’s All One Case: The Illustrated Ross Macdonald Archives, by Paul Nelson and Kevin Avery, with Jeff Wong and we appreciate the editors for giving us permission to print this.)

PAUL NELSON: In an interview you made a point about Raymond Chandler that really puzzled me: “Raymond Chandler has shown how a private detective could be used to block off over-personal excitements while getting on with the story.” I never felt that way with Chandler, and that seems to be somewhat of what you’re saying now in connection with your work.

ROSS MACDONALD: Well, I ask you simply to compare the Chandler of the stories as represented by Marlowe with the Chandler who wrote his letters. You see the difference? There’s a much wider range of feeling in the letters than there is in the man in the story. A really remarkable range of feeling. By “over-personal excitements” I mean over-personal in terms of fiction. When he tried to get too much of his self-feelings into his fiction, it didn’t work. You have to dole it out very carefully if you’re the kind of writer that Chandler is—a writer of sensibility, almost of sentiment really. What I’ve just been saying about Chandler is true of myself in some degree, although we don’t share the same psychic structures or anything like that. Far from it.

There’s one sense in which the hard-boiled style, so-called, is a device which saves the writer from getting too deeply, too personally, involved with the characters. It stands between him and the characters and what happens to them, and it gives you a certain objectivity because the subjective element is sort of filtered off into the detective figure. But in the long run all these books, Chandler’s and mine, are totally subjective really. I’m talking about strategies of getting them written and getting the stories told. I’m not talking about the ultimate fact that the stories are lyrical and subjective from beginning to end. But if you went at it directly, saying to yourself and the reader, “This is a lyrical and subjective account of life in Southern California,” it wouldn’t come off. You can’t write fiction that way. Fiction is composed of endless stratagems, avoiding the over-personal. Most failed writers in fiction are people who never found out how to avoid the over-personal. Then of course there are others who never found out how to get the personal in at all, and that’s worse.

PAUL NELSON: Philip Marlowe wasn’t ever used up the way Sam Spade was.

ROSS MACDONALD: Marlowe, as I say, is another story, which I’m not prepared to tell. I haven’t reread Chandler for a long time, and I don’t take Chandler’s overall intentions as seriously as I take his line by line style, which I think is really admirable. I’ve never found his books as morally interesting as I do The Maltese Falcon.

PAUL NELSON: One could argue that Marlowe doesn’t really probably take a risk in any of the books until The Long Goodbye.

ROSS MACDONALD: I was just going to say that. The Long Goodbye is the only one where the risk is real. He really does lay himself on the line in love and friendship for a bad man. It’s a somewhat similar situation to The Maltese Falcon. On the other hand, I don’t consider The Long Goodbye to be a wholly successful work.

PAUL NELSON: What don’t you consider successful about it?

ROSS MACDONALD: Well, it just doesn’t have the strength and the movement and the style and the flair that his earlier books do. For me. I recognize its riches, but they are not quite primarily the virtues of a really good detective story. It’s a book which is almost a new kind of creation.

PAUL NELSON: If you can classify Dostoyevsky as a detective writer, I don’t see why you exclude The Long Goodbye from being—

ROSS MACDONALD: No, I’m not excluding it, I’m comparing it with his earlier books. Naturally, it’s a detective story, but it doesn’t obey the same rules as his earlier books. Wouldn’t you say that he was deliberately trying to change the form in that book? Incorporate into it material that he had never touched before and so on?

PAUL NELSON: Yes, I would.

ROSS MACDONALD: Well, you have to remember that I’m talking about Chandler as a combination disciple and competitor. He’s pretty close to me, and I’m really talking about what I would choose to do. I don’t particularly mean to criticize him.

PAUL NELSON: Do you feel that the idea of “fiction as action” works less well with Chandler?

ROSS MACDONALD: Oh yeah, I think Chandler’s writing in a much older form. To put it very obviously, his detective is a conscious self-image, but not intended to represent the complexities or the realities of the author’s own nature or even his perceptions, is the way I feel about it. I feel that the whole thing is at least one remove from Chandler. It’s natural that he should write that way because his subject really is the loss of the unitary central personality. It’s what he’s writing against, so to speak, in Marlowe. He’s not intended to be a self-image—he’s quite remote from the reality of Chandler—and Chandler wasn’t really putting himself on record or on the line in the person of Marlowe. And Marlowe is a Romantic figure, quite intentionally so. The other characters are even more remote from Chandler. It’s what I would call truly Romantic fiction, in the sense that he’s not really aiming at a personal reality. In fact, he’s writing something that could be described almost as a pastiche—a brilliant and witty pastiche. I really don’t regard him as a realistic writer. I don’t think he was planning to be.