HOW I SHOT THE SPHINX

I first went to Egypt in 2005 to shoot a helicopter shot of the Sphinx for a Hollywood action movie. I remember stepping off the plane behind an Egyptian family from Great Neck, Long Island.

“I can’t believe I’m in Egypt!” the teenage daughter kept repeating in an accent as Jewish as any Bat Mitzvah girl from the Five Towns. “I can’t believe I’m in Egypt!”

Neither could I.

“Wait, just wait till you drink the water from the Nile,” said the mother in the same Jewish accent. “Then you’ll believe you’re in Egypt.”

On that romantic arrival, I felt that somehow my journey to the land of the pyramids would not be an easy one. It wasn’t. I was traveling with seventeen cases containing the Spacecam, a rare and expensive gyrostablized camera that mounts on the front of a helicopter, which the customs inspectors confiscated under the watchful eye of a portrait of President Hosni Mubarak.

I spent days trying to reclaim the Spacecam, waiting on lines, seeing minor officials. I paid small fees to process applications in Arabic that I couldn’t read.

During those days, I had one of the strangest meetings of my life. I went to see the head of customs at the Cairo International Airport, a general. I drank mint tea and waited in a chair in front of his desk for half an hour while an Egyptian soap opera droned in the background on an old Russian black-and-white TV. The general looked up from his paperwork from time to time and smiled at me. I smiled back, not a word exchanged. After half an hour, he looked up and said, “Do you like George Bush?”

Was he was testing me? I didn’t want to give the wrong answer. I thought hard for a moment and said: “I think Bush made a mistake going into Iraq, a big mistake.”

The general smiled a wide, delighted smile. “You are good man. I give you your camera.” Then he added: “Saddam is great man.”

We had to reapply to Defense Minister Tantawi for another flight date around the head of the Sphinx. We were given another date a week later. If that expedited date was on account of any money changing hands, I never knew and never asked.

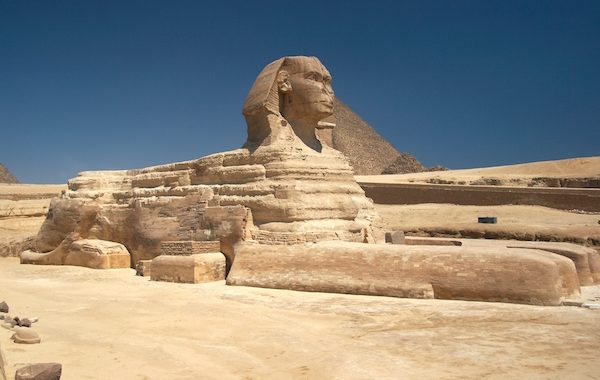

We did fly our historic mission starting low down in the valley near the Sphinx. We’d fly just in front of it, then climb up, passing the tops of the pyramids in a line. The pilots flew so low that the helicopter, a massive Soviet MI-17 about the size of a bus, kicked up a cyclone of dust. Inadvertently, we chased hundreds of tourists every which way as we climbed up to the plateau of Giza and the vast desert beyond. Tourists took cover in the bus parking lot, only to find themselves trapped between the buses as our 60-mph rotor wash blew a torrent of desert sandstorm into their faces.

The following day, the Supreme Military Council forbade anyone to fly around the Sphinx in a helicopter ever again.

When I returned to Egypt in 2009 to prep another film, I sensed a palpable mood change in the country.

Over breakfast, I read in the morning paper about a man pulled over in his car by two policemen. They stole his cell phone and 165 Egyptian pounds, about $35. The next day the man went to the police station to complain. The day after that, the two policemen came to his apartment and threw him out his window to his death. Sentenced to two years in prison, I doubt that the policemen actually served that much time, if any.

Due to disagreements well described in the novel, we switched production companies, not an easy thing to do in Egypt.

One of the eeriest sensations I’ve ever had was on the night I saw the original Egyptian producer. We had paid him a large amount of money that had yet to be spent on the film. I demanded the money back. He insisted that we meet out at his country club in the middle of the night where we could sit under the watchful eye of an armed guard at the front door and a night porter who could witness us together. He would only sit in sight of this guard. There were no other members in the club at that hour.

He was nervous. He refused to return the money to the production, but still he was very frightened. I realized that he was physically frightened of me. I believe that he was prepared for me to kidnap him or kill him over the money. Witnessing this fear was so bizarre to me. I’m one of the least threatening people I know. I’ve never even punched anyone in my life. Why was he afraid? Was it because I was American? Had Iraq and Afghanistan, U.S. raids in the middle of the night, the extrajudicial targeted assassinations, the drones in Yemen and Pakistan, and the mistakes—the dead women and children and parents in wedding parties and funerals—made me a source of terror? Had the War on Terror made me an object of fear? I believe so.

Shooting the Sphinx is based on personal experiences, but it is a fictional account. No one was murdered because of the movies I made. The revolution did not interrupt our filming.

However, you can taste fear when you see it, smell it even. For me it was an intoxicating moment, one to back away from for sure. Yet I can now see how seductive it becomes, when one is presented with the easy temptation to solve a problem by paying money to a pesky policeman or a customs official or even a general, whether it’s simply to get an official to just do his job on time, or to make some troublesome person disappear.